As vehicle technicians, and business owners, we regularly come across a concept or failure that we have not seen before. This is a result of the constant evolution of our trade, and whilst the concept of burning fossil fuels to produce energy for propulsion is a ‘given’ loose foundation, the way it is achieved,

the bi-products that are produced and their management, have changed significantly over my period of tenure in the trade, which for reference is ‘post-war’ in case you were wondering! Since the introduction of new emission standards, the bar is continually being set higher, from its origins as Euro 1 to the most recent, EU6. We all know the reasons behind the initiatives, and whether we agree or disagree with them, I am writing about the fault and fix strategy rather than the politics and legislation.

We recently received an Audi Q5 with some warnings present on the dashboard which the customer wanted to resolve. The warnings present were the engine management system light, the coil/glow plug warning light, and a message in the centre dash display warning of an AdBlue system fault and

a remaining range to no restart. As usual, capturing as much information from the customer is pertinent to assisting with hypothesis creation, and making sure we have ‘all’ the facts before heading down a path.

In this instance, the customer was transparent. We were the first garage to look into it and the report was as follows: ‘The remaining range light came on saying AdBlue range 1,500 miles to no restart, we’ve topped up the AdBlue to full, the light didn’t extinguish and then halved in range, turned from an informative MMI message to a yellow warning, indicating a system fault and 600 miles to no restart. In the days following making the appointment but continuing to use the vehicle cautiously, the engine management light appeared on the dash, but the car appears to be driving OK’. Plenty of information to begin our evaluation.

Standard procedure in any engine management or emissions related fault is to acquire an initial capture of faults using a suitable scan tool for speed and convenience. From there, boiling the kettle and pulling up a pew at the desk in front of the PC is the next port of call. Creating a plan of testing, looking for any cluster fault patterns in individual controllers, or multiple controllers, and gaining some understanding of the system and its operational properties.

Embracing change

Pertinent to add at this point would be a technician’s awareness of new technology or systems. We all remember that some garage folk were of the attitude when diesel arrived that ‘they wouldn’t be doing diesel, it’s a phase/fad,’ and they couldn’t have been more wrong. Our business by volume currently sees around 75% of its engine management diagnosis/repair work as diesel, despite the recent improved efficiency and popularity of GDI petrol derivatives. We are in a similar phase change currently with the not-so-recent shift to becoming proficient in high voltage vehicles. Again, we are seeing some archaic views that it will be another fad, and whilst I remain indifferent in the political debate of the saga of ‘to do EV or not,’ my motivation is less emotive. At 37 years of age, and 20 years into my life sentence (career), I am fairly committed to the trade, profession, and our business. I am happy to embrace change and development for one sole reason. It drives footfall through our door and helps me pay my bills and my staff. It is also quite interesting to learn about these

things, even though sometimes they can give you a torrid time and some real brain-ache. Some may say I have narrowed our potential footfall by restricting the bandwidth of vehicle brands we work on, but this is through technical experience, suitable tooling investment and product knowledge (plus a small love affair). We’d all like to be the technicians of old, everything to everyone, but as the customer was once ‘the customer’, now in a sense the car is ‘the customer’ to our business.

The greater point about awareness and competency here is I often read the vast array of technical chat and posts within online automotive forums. There have been numerous posts on AdBlue faults on Volkswagen Audi Group vehicles – how to troubleshoot them, particularly in the presence of no fault

codes, with just a warning message stored on the driver display. ‘It could be this, it could be that, is software an area of concern…’ The more complicated things get, the more we are expected to know and be proficient in. I mean we’re mechanics, right? Training is out there for Selective Catalyst Reduction systems (when we get back to face to face training), and despite reasonable product awareness and function through self-study (using resources such as Alldata and Erwin) I do still feel my knowledge could be improved in this area. I have attended a great course on DPF, EU6 and SCR systems through the AutoCare Garage Network, which was presented by the very knowledgeable (and likeable) Ant Taylor, and it filled some voids in my knowledge and offered some useful tips. In addition, I was booked on the highly regarded ADS David Massey DPF/SCR course last summer (you can never have too much training, right?) Unfortunately, we all know what happened last summer. The point is, repairing cars continues as we are fortunate enough to be able to open and trade. It can be a tough old place to know what you have/need to know.

Gathering data

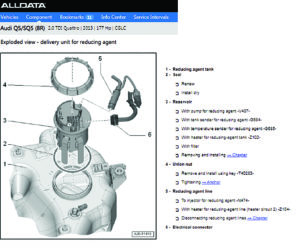

With that in mind, we return to the data and basic detail of system function and layout. There are plenty of aftermarket data suppliers out there, as well as the manufacturer’s resource. Before committing to a token purchase via the manufacturer portal I checked what information was present in Alldata for the vehicle and its systems. It was information rich and gave me a good idea of the components fitted and their locations. A tip here, particularly prominent with the German manufacturers, you need to think and search like its written by them. In terms of searching AdBlue, you won’t necessarily return results you want, if any. But change that to SCR (Selective Catalyst Reduction), or reduction fluid, and you will find plenty of useful information. A common fall down with manufacturer data is unless you think like it is written, you might feel your data supplier hasn’t got it. Alternatively, you can send an information request to Alldata, with a good response time in getting what you need.

Armed with some knowledge and some basic data, I put my cup of tea to one side and dived in. The faults present in the engine ECU were:

P204700 Reductant injection valve circuit open Passive/sporadic

P204900 Reductant injection valve circuit high Passive/Sporadic

P20BD00 Reductant heater “B” Control circuit Open Active/Static

P20BD00 Reductant Heater “B” control circuit open Active/Static.

We then raised the vehicle on a lift to look at the system and its components (all mounted on the underside of this vehicle) and gained some useful insights.

The reducing agent injector could be seen and there was a clear stream of crystalised reduction fluid around it and the connection to the exhaust system. The wiring harness to the top of the injector was damaged, showing broken, exposed wiring. Things were starting to fall in to place easier than one

might have thought.

Mindful that we may have a secondary issue to the injector, we needed to see what the heater circuit was doing and to check the function of the delivery module. The reason for foresight here, is we had been able to identify a clear and present issue but having been frustrated in the past by a lack of foresight to the road to a ‘complete’ repair, applying these tests/measurements at this point will allow clarity in financial outlay for the customer. Much better than making the dreaded call we’ve all had to make at some point to explain ‘it also needs…’, which always makes me feel like I’m the bad guy. I’m always going to be the bearer of bad news, but I’d like it to be as accurate as possible in terms of what the customer’s risk to exposure is.

We set up a test by removing the reduction fluid injector and suspended it into a measuring container whilst connected to the fluid line and, hence, tank. We carried out a final control output test on the delivery module. We could hear activity in the tank which was a good start. We added to the final control output and duty cycled both the injector and the unit to build pressure for delivery. What we were able to observe is poor spray pattern/dribbling from the injector but confirmed pressure delivery in ‘some guise’ from the unit itself. Another useful tip here, is don’t believe all you see.

These VAG injectors have 5 or 6 eyelets for pressure delivery. In all tested examples so far (including new confirmed fixes) only two fired. Don’t be misled, this is correct operation.

Were there other faults waiting in the wings?

Further wiring checks across the external mounted plug for the delivery module enabled us to confirm the compromised integrity of the heater circuit within the delivery unit, and the pressure sensor within the unit was high resistance. This did not manifest as a fault, but when looking at the plausibility

of the pressure sensor in live data it was measuring -73hpa. A degree of vacuum could be considered plausible after a long period of inactivity but given the fact we had just run the delivery unit, and in theory proved pressure generation possible within the system, this lack of pressure change suggested that the delivery unit had other faults present ‘waiting in the wings’. If this had not been considered, come the time of stress-testing the system for correct function, we would have flagged a pressure generation/monitoring fault – this element is purely brand failure experience led, but a good discipline for the multi brand technicians reading.

The wiring connection compromised for the heater at the reduction fluid injector unfortunately meant a new section of hose from front to rear was the manufacturer repair. One new fluid line, injector, gasket and delivery unit later, coupled with 18 litres of fresh reduction fluid, authorised for repair, we were ready for the next stage.

New reduction injector after fitment

The nuts and bolts of this repair were fairly straightforward – the biggest challenge (proven by every delivery module I’ve done on VAG cars) was the twist-on plastic nut (like an in-tank fuel pump). For some reason, they really don’t like coming off in one piece, probably why they are listed as a ‘frequently order together’ parts listing on the EPC.

The post-repair element of this job is just as important as the diagnosis in my opinion and sometimes a concept that we technicians overlook. It’s had the new part fitted right? Why is it not fixed?

At this stage, we now had a car with shiny new parts, that worked under final control diagnosis, but the AdBlue warning light remained on the dashboard. To proceed, we needed a diagnostic tool capable of carrying out the necessary adaptions and initialisations/test processes to validate through the car’s eyes, that it is in fact fixed. This is where VAG group cars can be a bit of a pain and referring back to the diagnostic part of our process is key to success as a technician, and as a profitable business. If you have no faults in the system but warnings present at the diagnosis stage, there is a very good chance someone has already been in there, cleared the engine management or reduction agent module fault entries. This will give you a bum steer, because it could take up to an hour of varied driving in some cases on certain models for the DTC to return again. The reason being is it needs time to carry out efficiency tests of the SCR system to appraise the area of failure or concern, or alternatively, in the case of successful repair, successful operation. Who is paying for the time and labour, just to get the DTC’s back?

The resetting or relearning element, contrary to common belief, is not always autonomous, even with new parts fitted and data reading correctly. In example A, whereby the adblue fluid level has reached a low level, like fuel, but its last known state was working, topping up will indeed, after the observed test period, with a successful SCR efficiency test (performed as a background process by the car), self-extinguish. This is autonomous.

In example B, whereby the adblue system has reached a low remaining range before restart through reasons of faults and key cycles elapsed since setting a DTC, rather than reduction fluid level, rectification cannot be achieved autonomously.

Final checks

Knowing this, we began the close out phase of the repair. I started with a clear down of all faults from the affected controllers and no return was observed. Next, using a scan tool (in this case, I used ODIS) a control unit function in reductant control module was initiated for ‘inductment of reducing agent’. The process on the scan tool is guided, making statements, observations, and test requirements clear. The guts of this part of the process are for the car to see the fluid dosed accordingly from the delivery unit to the injector, to be injected, and its function subsequently validated by emissions reduction (specifically NOX) in the exhaust system, monitored by a NOX sensor. The NOX sensor ultimately then feeds back that successful reduction by means of lower measured NOX content when dosing has taken place and is validation the SCR is working correctly.

In some VAG cases, the light may still be active on the dash at this point. For this, there is a specific function on ODIS to reset the faulted state by means of Q&A between operative and scan tool, further measures could be software related, or TSB driven. In my case, the feedback from the SCR test was good and meant I could rest easy in the knowledge the light was extinguished, the system was operating correctly and that the process was stress tested to ensure longevity of ‘fix’.

Resources: